This is the first post in what we hope will be a fairly regular blog showcasing some of our work-in-progress on the project. While we develop focused research for publication, we hope the blog format will enable us to highlight some of the breadth of material available from Exeter in the early-modern period. As our project hopes to rebalance the centrality of London in studies of the period’s literature, one simple aim of this blog will be to show the rich literary sources available when we focus on a local centre like Exeter. This first post reflects on the aims of the project in light of the launch seminar we ran on 1st December 2021 at the University of Exeter’s Centre for Early Modern Studies. We were pleased to welcome a good-sized audience, especially via Zoom, and including several members of our advisory panel.

The event began with an introduction by Philip Schwyzer. Philip pointed out that our project title, ‘Writing Religious Conflict and Community’, is calculated to attract attention from an audience wider than those who are normally interested in early-modern studies. A challenge for us, therefore, as we move through the project will be to reflect on what our research offers to an audience with general or ‘presentist’ interests. This proved to be the case on the night in question, when we were asked why we had picked out the period 1500–1750 in particular. From our specialist standpoint, it is easy for us to oblige by listing the momentous events within the period’s successive religious upheavals in which Exeter played a central role (cf. the front page of this website!). Yet, in a sense, this simply begs the question: why are we so convinced that these events are of wider interest? One part of the answer is that uncovering a longer history of religious factionalism could help to contextualize questions of identity and community cohesion that remain urgent today.

Another question raised by our title is what exactly ‘Conflict’ has to do with ‘Community’. Clearly there was a great deal of religious conflict in our chosen period; but equally the story of early-modern religion (or for present-day religion for that matter) is not only about conflict. Religion is so vital to understanding the early-modern period because it forces us to reckon with how deeply belief can shape people’s actions and identities. This might include not only national, cultural, emotional, or economic experiences – but also, as we argue in this project, a sense of place, of civic and local identity. At the same time, in a period of highly combustible religious politics, a strong sense of communal religious identity can in itself be a driver of conflict. At various times, Exeter was the scene of several groups who defined their religious identity, often in violent terms, through distinction against rivals, even perceived enemies.

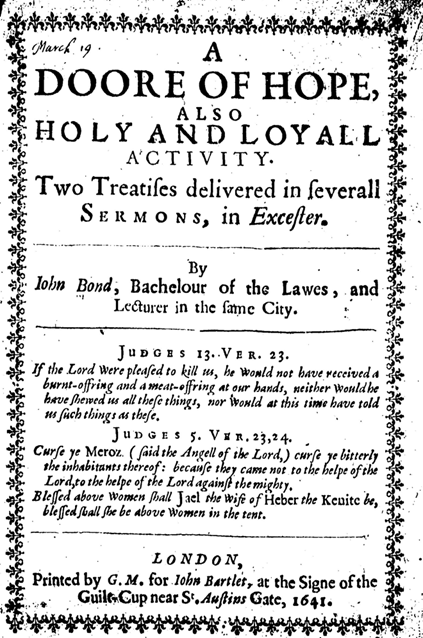

This dynamic between community and conflict was evident in the first of two research papers presented by our team at the launch seminar. Niall Allsopp introduced his work in progress on two writers of the civil war period who engaged in Exeter on opposite sides of the conflict. John Bond’s sermons sought to galvanize his parishioners and fellow-citizens on the side of parliament. Bond’s efforts consciously formed a local branch of parliament’s nationwide mobilization, but at the same time tied to a distinctive sense of identity for the Protestants of Devon and Exeter. By contrast, Robert Herrick’s poems celebrated the entry of King Charles I and other royalist dignitaries to the city after it had fallen to the royalists. Herrick used a very different style of religious language – heavy with liturgical symbolism – to sanctify the links between Exeter’s citizens and royal government. Both texts present fluent and compelling images of a harmonious community, yet only by reading them against each other can we reveal how their visions insist on their violent incompatibility with the alternative.

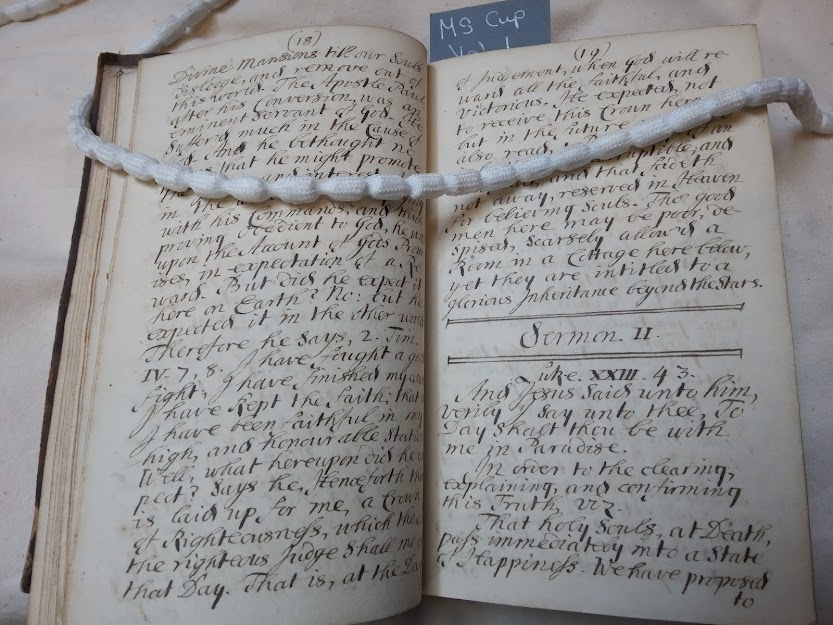

David Parry’s presentation focused on a remarkable collection of as yet unstudied manuscript sermons by Exeter Dissenting ministers found in the archives of the Devon and Exeter Institution. Among the roughly 4500 pages of sermons are those attributed to Joseph Hallett II (1656–1722), Joseph Hallett III (bap. 1691, d. 1744), and James Peirce (1674–1726). All three of these ministers were prominent on the ‘Arian’ side of the Exeter Arian Controversy over subscription to the doctrine of the Trinity that led to divisions not only in the Exeter Dissenting community but across English Nonconformity. However, while a minority of their sermons expound their heterodox views of the Trinity, the majority express concerns common to Protestant Dissenters in the period, including the everyday piety of Scripture reading, prayer and sermon hearing, critiques of the ceremonialism and intolerance of the established Church, and the consolations of the afterlife.

Among these sermons are three commemorating the Gunpowder Plot that illustrate the complicated triangular relationships between the established Church of England, Protestant Dissenters, and Roman Catholics. While Joseph Hallett III sees the failure of the Gunpowder Plot as a providential deliverance from the tyranny of ‘popery’, he also argues for a religious toleration that includes Roman Catholics. In another sermon, Hallett’s defence of religious toleration extends beyond competing versions of Christianity to include Muslims, gesturing towards the wider scope of religious diversity beyond as well as within Christianity that this project will engage.

More on all of these issues to follow in future posts, along with a wider range of insights into the process of research and the breadth of materials available to us. One more reflection on this breadth: one thing we have become increasingly conscious of during the project’s first few months is how much we will not be able to cover drawing on the resources of the project team alone. To arrive at a fully representative picture of religious identity in literature of this period, we will also be calling on collaborators, participants, and contributors to future conferences and publications. Expressions of interest are welcome, as are questions from readers.

Niall Allsopp and David Parry