One strand of the ReConEx project is the role of preaching and sermons within the varied religious communities of Exeter from 1500 to 1750. My current research focus within this strand of the project is indebted to a discovery by one of our project advisors, Paul Auchterlonie, who has identified within the holdings of the Devon and Exeter Institution eleven volumes of bound manuscript notebooks transcribing Exeter Nonconformist sermons of the later seventeenth and early eighteenth century. These sermons are a rich resource, illustrating everyday piety and religious practice among Exeter Dissenters while also touching on matters of religious controversy in the period.

While many of these sermons are unattributed, many of those that are assigned a preacher are attributed to Joseph Hallett II (1656–1722), who, along with his father and son of the same name was a prominent Dissenting minister. Joseph Hallett II is a key transitional figure in the history of Exeter Dissent – like his father Joseph Hallett I (c. 1628–1689), Joseph Hallett II was a Presbyterian minister and co-pastor of Exeter’s largest Presbyterian congregation James’s Meeting. However, in the wake of the ‘Arian controversy’ of 1716–19 among Exeter Dissenters, Hallett’s refusal to subscribe to extra-scriptural formulae designed to protect orthodox Trinitarian doctrine led to his ejection from his ministry at James’s Meeting and the establishment of the rival ‘Arian’ Mint Meeting, where his son Joseph Hallett III (c.1691–1744) in turn served as minister.

I will be mining the riches of these unstudied sermons for some time to come, but today I would like to draw attention to a surprising connection that jumped out at me between one of Hallett’s sermons and the writings of C. S. Lewis, the twentieth-century literary scholar and Christian apologist best known for the Chronicles of Narnia.

The first set of sermons in volume 1 of the eleven notebooks is a series of six sermons on Jesus’ words to the repentant thief on the cross: ‘And Jesus said unto him, verily I say unto thee, To day shalt thou be with me in Paradise’ (Luke 23:43). Hallett’s exposition moves beyond the immediate context of this text to expound a number of points relating to the afterlife across multiple sermons. As with other sermons in these volumes, Hallett’s sermons on this text combine close reading of the original biblical context, pastoral consolation and encouragement to his hearers, and polemical refutations of those who differ from Reformed Protestant orthodoxy.

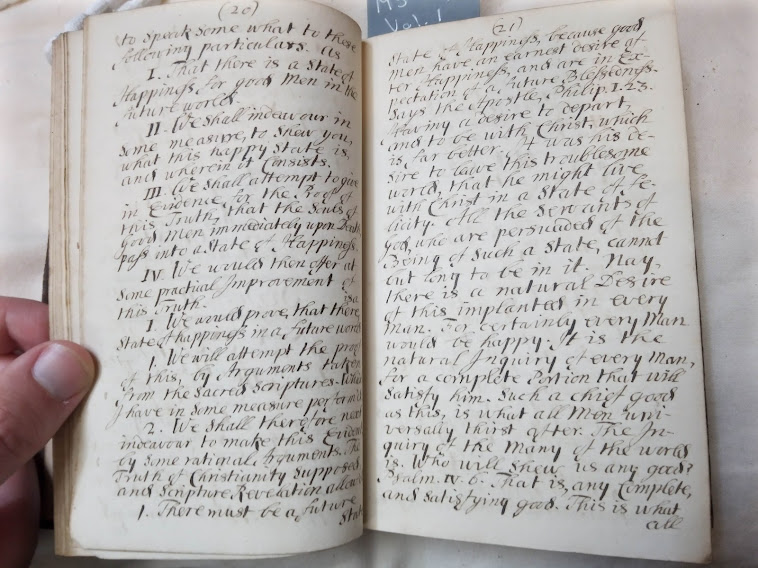

Sermon 2 in the series focuses on arguing that ‘There is a state of Happiness for good Men in the future world’ (p. 20). While also citing biblical texts, Hallett develops an argument from human experience for a Christian view of a happy afterlife at least for some, in what we could call a natural or existential apologetic:

There must be a future State of Happiness, because good Men have an earnest desire after Happiness, and are in Expectation of a future Blessedness […]

Nay, there is a natural Desire of this implanted in every Man. For certainly every Man would be happy. It is the natural Inquiry of every Man, for a complete Portion that will satisfy him. Such a chief good as this, is what all Men universally thirst after. The Inquiry of the Many of the world is. Who will shew us any good? Psalm IV.6. That is, any Complete, and satisfying good. This is what all universally would be possessed of. (pp. 20–22)

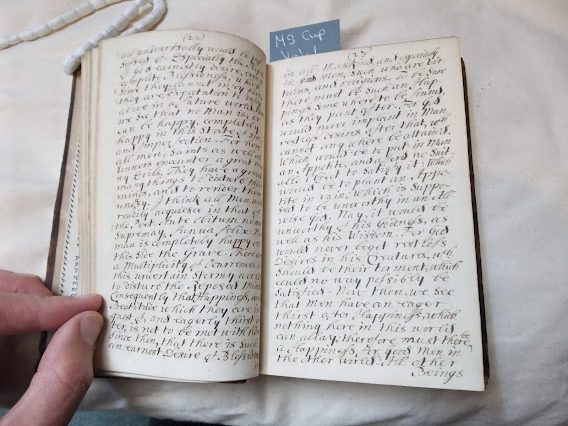

Yet although this desire is a universal desire of all people, it is not one that is fulfilled in our experience of this life, because

no Man is, or can be happy, in this State of Sin and Imperfection. For here all Men, Saints as well as Sinners encounter a great many Evils. They have a great many things to disturb their Minds, and to render them uneasy. (p. 22).

However, the existence of a desire that cannot be satisfied in this world, Hallett argues, points to the existence of another world in which it will be satisfied:

Since then, that there is such an earnest Desire of Blessedness in all Mankind, and especially in Good Men, such who are virtuous and religious, To be sure there must be an Happiness some where as they pant after. For God would never implant in Man restless desires after that, which cannot any where be attain’d. […]

Now then, we see that Men have an eager Thirst after Happiness, which nothing here in this world can allay; therefore must there be a Happiness for Good Men in the other world. (p. 23)

When reading this sermon, I was struck by the similarity of Hallett’s line of argument with an argument often found in the writings of C. S. Lewis. Lewis draws on the Romantic idea of Sehnsucht, a longing or yearning for some undefined happiness or perfection, a longing to which Lewis gave the name ‘Joy’ (hence the title of his spiritual autobiography Surprised by Joy). For Lewis, glimpses of this happiness for which we yearn can be experienced through such things as nature, favourite books and deep friendships, but these experiences also carry with them a yearning for a completion of this joy that is never fully satisfied in this life. This line of argument is pervasive in Lewis’s work – one place where it is expressed concisely is in this passage from Lewis’s bestselling apologetic work Mere Christianity:

The Christian says, ‘Creatures are not born with desires unless satisfaction for those desires exists. A baby feels hunger: well, there is such a thing as food. A duckling wants to swim: well, there is such a thing as water. Men feel sexual desire: well, there is such a thing as sex. If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world. If none of my earthly pleasures satisfy it, that does not prove that the universe is a fraud. Probably earthly pleasures were never meant to satisfy it, but only to arouse it, to suggest the real thing. If that is so, I must take care, on the one hand, never to despise, or be unthankful for, these earthly blessings, and on the other, never to mistake them for the something else of which they are only a kind of copy, or echo, or mirage. I must keep alive in myself the desire for my true country, which I shall not find till after death; I must never let it get snowed under or turned aside; I must make it the main object of life to press on to that other country and to help others to do the same.’[1]

I am unaware of any evidence that Lewis was aware of Hallett’s sermon. I suspect it is unlikely, though we do know that Lewis’s prolific reading included some seventeenth-century Nonconformists. The title of Mere Christianity, expressing Lewis’s desire to defend the core of the Christian faith shared across confessional divides and to avoid matters of inter-denominational controversy, was taken from the moderate Presbyterian minister Richard Baxter’s description of himself as a ‘mere Christian’, as Lewis acknowledges in his preface.[2] In his capacity as a literary scholar, Lewis also wrote an essay on John Bunyan, author of The Pilgrim’s Progress.[3] If there is any evidence that readers know of that Lewis was aware of Hallett or of this sermon, I would be glad to hear of it. It seems instead either that Lewis and Hallett arrived at a similar argument for a Christian view of the afterlife from reflecting on human experience, or else that their arguments share a common ancestor transmitted down through the history of Christian apologetics in preaching or writing. I would be glad to hear any suggestions of the missing link.

Sermon MS images reproduced courtesy of the Devon and Exeter Institution.

[1] C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (1952; repr. HarperCollins, 2001), pp. 136–7.

[2] Lewis, Mere Christianity, p. ix. Baxter calls himself ‘a CHRISTIAN, a MEER CHRISTIAN, of no other Religion’ in Church-History of the Government of Bishops and their Councils Abbreviated (London, 1680), sig. (b)1r. Lewis also uses the term ‘mere Christians’ in a letter to the Church Times of 8 February 1952 to describe the shared commitment of the Anglo-Catholic and Evangelical wings of the Church of England to the supernatural character of Christianity in opposition to anti-miraculous tendencies in some liberal theology. For more on connections between Baxter and Lewis, see N. H. Keeble, ‘C.S. Lewis, Richard Baxter, and “Mere Christianity”’, Christianity & Literature 30.3 (June 1981) 27–44.

[3] C. S. Lewis, ‘The Vision of John Bunyan’, in Selected Literary Essays, ed. Walter Hooper (Cambridge University Press, 1969), 146–53.