Centre and Locality

If you were a writer in Exeter and wished to get your work published, in the early modern period you had to send it to London. Except for the universities in Oxford and Cambridge, barely any printing took place outside of the capital until the very late seventeenth century. One exception—and it is really exceptional—was the period around 1644-1648 when a printing press operated in Exeter. But only a handful of extant titles can be identified as having been printed on it (hopefully to be discussed in a future blogpost). Far more Exeter-related works were printed in the same years in London.

In order to study writings produced in or related to early-modern Exeter, it’s obviously necessary to find them first. In this post, I want to try to describe the research methods I’m using to identify ‘Exeter-related’ texts. It’s an attempt to think through the assumptions I’ve relied on—hopefully making them appear relatively systematic—and the contexts I’ll need to make sense of my findings.

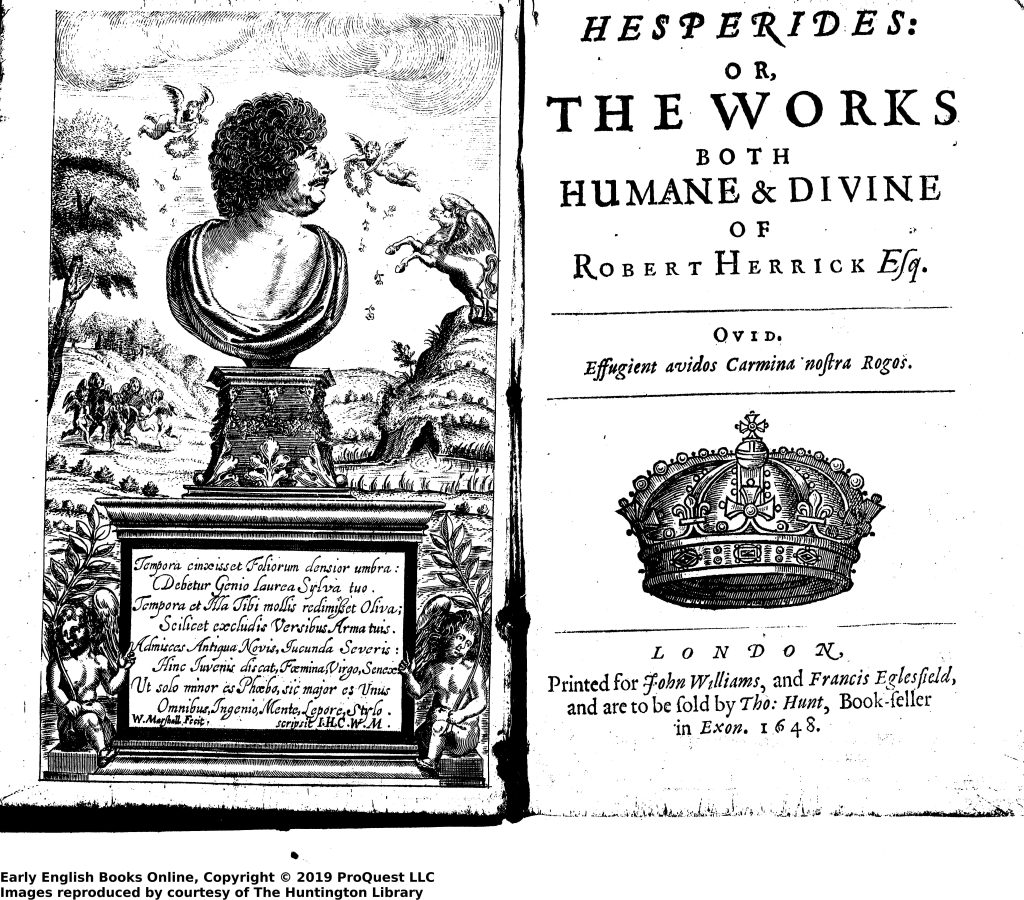

About the Exeter book trade we know a great deal, thanks in large part to the work of Ian Maxted, generously available online in his ‘Exeter Working Papers in Book History’. We know about Exeter booksellers like Michael Harte, the contents of whose bookstall can be reconstructed from his 1615 inventory. Many Exeter booksellers had served apprenticeships with London stationers, and maintained close links in arranging for books printed in London to be sold in Devon. This includes the Exeter-related text I—as a literary scholar, not a book historian—get most excited about: Robert Herrick’s poetry collection Hesperides (1648), of which some copies were ‘Printed for John Williams and Francis Eglesfield and to be sold by Tho: Hunt, Book-seller in Exon’.

Gathering Data

As a first step, I have begun compiling a spreadsheet of ‘Exeter-related titles’ published during the English Civil Wars, between 1640 and 1660. The civil wars form my own specialist scholarly interest, but they are especially useful for this experiment because a plentiful sample of texts survives. This is partly thanks to the high volume of printing prompted by the national crisis and accompanying collapse of press censorship, and partly through the obsessive efforts of the book collector George Thomason.

A few caveats are needed: the 1640s and 1650s were obviously unrepresentative decades in many ways, and it is equally arbitrary to treat Exeter in isolation. Trade in books between London and Devon persisted throughout the longer period, and that Exeter was only one point in a regional network that included other important towns like Plymouth and Barnstaple. These contexts are essential to making sense of my results, locating my survey within neighbouring decades, the 1630s and 1660s, and neighbouring areas in Devon. It could also be argued that focusing only on print arbitrarily excludes works circulated in manuscript. That was the format, after all, in which almost all of the texts I’m interested in must have been initially transmitted to their London printers.

Book trade links are obviously an important part of the picture, but I hope our research will also explore a broader range of literary and historic ways in which texts might be ‘Exeter-related’. These might include authors with Exeter and Devon connections which shaped their thinking at the time of writing; or books whose title-pages tell us they were written in Exeter but transmitted to London.

As an initial, somewhat rough-and-ready experiment, I have tried searching ‘Exeter’ in the default ‘basic’ search of the database Early English Books Online for the period 1640-1660. This search picks up fields from the title page (title, author, ‘imprint’ or printing information), and it automatically includes spelling variants, the then-interchangeable forms ‘Exceter’ and ‘Excester’. Some human intervention still remains necessary, for example to discover separate cases of ‘Exon’, or, alternatively, to filter out ‘white noise’ from Exeter College, Oxford. And further interpretive questions remain: how, for example, to categorize news pamphlets whose title-pages include brief mentions of Exeter; or authors like Joseph Hall, the former Bishop of Exeter, who moved in 1641 and thereafter engaged primarily with controversies in London (including with John Milton).

Thus far, with this relatively blunt and arbitrary method I have arrived at just over 80 items for my spreadsheet. I have tested that number by quickly running a similar survey on the same lines for Norwich, a city of comparable, slightly greater, size and importance in the period (and, coincidentally, Joseph Hall’s new see after he left Exeter). The cities have some strong similarities: both had vocal and fractious puritan communities, and both had well-established book trades. I ended up with 96 titles, an encouragingly similar ballpark to my figure for Exeter. Not all of this traffic is of quite the same nature: unlike Exeter, Norwich saw no military action, but made up for this with the intensity of factional controversy.

Interpreting the Data

This exercise has usefully suggested some of the many different ways in which a text might be ‘Exeter related’. Or, to put it another way, the many different kinds of connection between Exeter writers and their readers that are captured in civil war print. I hope to return to several of these categories as a starting point for further research, and in future blog posts:

- Texts transmitted to London which represent communities within the city in a certain way (e.g. puritan congregations), to presumed interested/sympathetic readers elsewhere.

- Texts which appeal to a wider audience as an escalation within local power-struggles.

- News reports by correspondents in or visitors to Exeter; documents promulgated in Exeter (proclamations, covenants) that demand attention at a regional or national level.

- Texts written by Exeter residents, commissioned for publication in London, for transportation back to Exeter and distribution among friends and followers (including ‘vanity’ publications).

- Texts which place an Exonian or Devonian ‘spin’ on familiar genres: sermons, supernatural encounters, biography, prison literature.

[1] See also: https://bookhistory.blogspot.com/2007/01/devon-book-36.html